A three-part study comparing retired pro football and hockey players with non-contact sports athletes finds no increase in the rate of early-onset dementia, researchers suggest.

The study, published recently in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, further suggests that chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)—a neurodegenerative disorder possibly linked to repeated concussions—may not be inevitable among contact sports athletes.

“The results underscore an apparent disconnect between public perceptions and evidence-based conclusions about the inevitability of CTE and the potential neurodegenerative effect on former athletes from contact sports,” according to an overview paper by Barry Willer, PhD, professor of psychiatry, and John Leddy, MD, medical director of the University at Buffalo Concussion Management Clinic and clinical professor of orthopaedics, both of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB, in a media release from Wolters Kluwer Health.

The study included 22 retired athletes, average age 56, who played at least two seasons in the National Hockey League (14 subjects) or National Football League (eight subjects). They all took formal tests for cognitive impairment or dementia; completed questionnaires assessing their executive function and mental health; and underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

The same examinations were performed in 21 male athletes of similar age who participated in non-contact sports (running or swimming). Most characteristics were similar between groups; the retired contact athletes had lower education, higher body mass index, and more injuries and other health problems.

On subjective questionnaires, the retired hockey and football players perceived themselves to have memory problems. They also rated themselves as having worse executive function (the ability to plan and carry out tasks), compared to the non-contact athletes.

But on standard neuropsychological tests, there were few differences between groups, and no overall differences in memory and executive function. Subjective ratings by spouses were also indistinguishable between groups, the release explains.

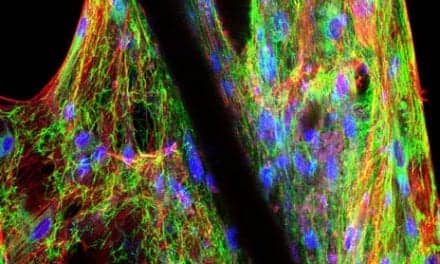

The rate of mild cognitive impairment—a possible precursor to dementia—was also similar between groups. Multimodal MRI scans showed no differences in brain structure and function. Experts in cognitive function and concussion concluded that none of the former athletes had dementia.

On beginning the study, Willer and colleagues expected that “some if not most” of the retired contact athletes would have dementia, and that the MRI scans would detect abnormalities consistent with dementia.

“Instead, our advanced brain imaging confirmed our findings that these former professional athletes were functioning according to age in each of the facets being evaluated.” Willer and coauthors write, the release continues. “It would appear that former athletes who volunteered for our study worried about their mental state and wanted to know, for themselves, whether playing their sport professionally had left them disadvantaged.”

The researchers took steps to ensure that their study was sensitive to the concerns of the participants; all of the retired athletes chose to receive feedback on their test results.

The researchers concluded that the findings provide some reason for reassurance that dementia and CTE are not inevitable outcomes for athletes who played contact sports at a high level.

“The results don’t argue against the existence of CTE, but do suggest that the risk is not as great as once believed,” Willer and colleagues write.

They emphasize the need for further studies to identify the factors, “genetic or otherwise,” that explain why some athletes are at higher risk of CTE than others, the release concludes.

[Source(s): Wolters Kluwer Health, EurekAlert]